Small Offerings

Beginnings

There was something in the way he raised his hand to thank the traffic as he crossed the road, open, confident, yet slightly apologetic. He was about seventeen, golden, a guitar case slung across his back. It was a few days before the lockdown. Days in which we teetered on the edge of something nebulous and unnerving. As he reached the bus stop he looked back at the traffic snaking at a crawl towards Crediton. He stuck out his thumb. I indicated to pull in to the bus stop as cars nudged past me, glad to gain a place in the queue.

His name was Jack and as we edged, along with the other commuters, towards Exeter, his phone pinging in his bag, he told me that he’d made the bass guitar that was now lying on the back seat and that today he was filming a promo with his friends at college. I learned that he’s not only talented at carpentry and music, but that he also enjoyed photography, the sciences, maths, humanities and design. We talked about his plans to study abroad – hopefully somewhere in Europe. His responses to my questions were earnest and sweet-natured; he spoke with the slightest of stutters, thanking me, several times, for stopping; ‘it’s kind of you,’ he said. I felt how much he had ahead of him – so many possibilities. I would probably never meet him again, but I felt protective of him, wanted good things for him. Would he still get them?

As we approached Cowley Bridge the sun came out and the traffic cleared. He pointed towards an ancient oak growing on the banks of the Creedy, ‘a tree surgeon told me that that’s the best tree in the whole of the UK’, he said. I hadn’t noticed it before but he was right, it was a beauty. I would always notice it now. As I dropped him off I felt a rush of connectedness and gratitude. And I wondered if moments like this would be possible in the world that was emerging. Because, as it turned out, it wasn’t just spring that had been waiting at the gate.

Adjusting

It is amazing how quickly a new normal can be established, but also how differently people react. It takes me a long time to adjust to change. For those first weeks I veered between the different stages of grief, in a kind of freefall as I grappled with working from home, Glen’s uncertain job situation and my family’s reluctance to come to safe harbour and isolate alongside us at the awkward house. Only with a week of leave from work have I moved to the acceptance stage. I am an introvert. I like to be alone. I can find the pressure of competition, to be achieving, to be out and ‘on’, overwhelming. For some time I have been fantasising about throwing a switch to bring everything to a juddering halt; an opportunity for a kind of recalibration. But the switch had been thrown and I felt afraid and untethered; the stop had come with an invidious threat that promised to rob us of our loved ones and freedoms. The calendar mocked me with its cancelled plans; poetry, work, birthdays, house plans – the stalled beginnings of new friendships. It took me weeks to unlearn its habitual checking and to accept that nothing meant the same anymore. Overnight the contemporary had become archaic, the everyday something to feel nostalgic about – ah, remember the days when we went to the pub, had coffees on street corners, hugged our friends? Perhaps this was what a global existential crisis looked like.

I allowed myself to wonder whether, alongside the horrors of financial hardship, rising domestic and child abuse, the sacrifices made by the disadvantaged and the undervalued, this could be an opportunity, collectively, for us to remember how to be.

Being here nowI wonder what will happen with the absence of touch, the ability to come together for celebration, ritual and gatherings, with the closing of spaces like churches, pubs, libraries; where one might go to find companionship or solace? I hear someone on the radio say that divinity comes from stillness and decide to try being still, without much success. I have always found solace in the outside. In moments of crisis the woods have been my church; wanting to lie down in the moss beneath a tree and give up the search for answers.

In Simon Reeve’s book, ‘The Life in my Journeys’ he suggests drawing a circle, a radius of five miles around where you live, on a map and getting to know every square inch. To come to know where you are. This is an idea I can work with. I decide to walk further, to try new paths, to notice more.

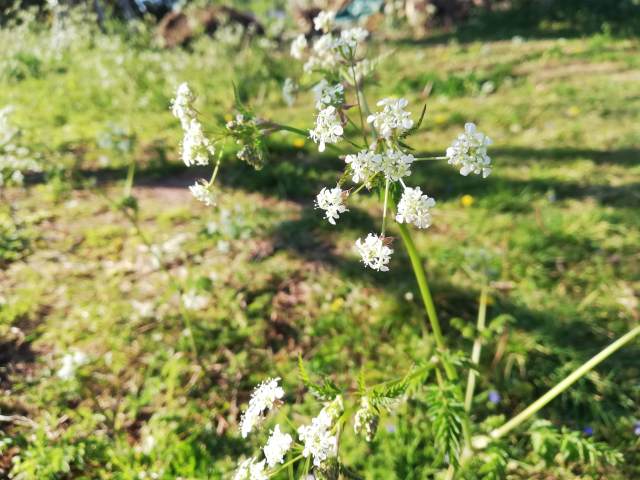

The hedgerows are twitching to life around the village and I walk the quiet consolation of the lanes looking at them, newly unafraid of speeding cars and vans in April’s bright, clear mornings. I have watched the tiny double-toothed new green leaves of the hazel unfurl, their undersides soft and downy, giving way here and there to stretches of prickly holly, the scrambling and twinings of honeysuckle. Cleavers rush upwards on tiny hooks as they stretch up the banks, dotted with starlike stitchwort. Bumble bee queens emerge from the soft earth of the banks, humming fatly as they seek out early nectar, Peacock butterflies flit between the egg yolk yellow dandelions, the bright splash of red campion and the froth of cow parsley. In the hedge I hear the squeak and rustle of busying mice and shrews.

People

Conversation outside of home has come to depend upon who we meet on walks, the nervousness of the first week when we shuffled mistrustfully past each other, dispensed with. We have all learned the new etiquette, giving each other a wide berth or stopping at 2 metres to talk. We meet a lady whose son is a frontline doctor and we talk of her anxiety at sending him off each day into the unknown, of whether she will be called back into school to teach before the summer is out.

In the field we meet Lizzie and her black labrador puppy Katy, who, Lizzie tells us, in the absence of her usually extended and varied walks, is bored. So we let the dogs play, shouting snatches of conversation between our carefully kept distances. Cooper loves Katy and we watch as they chase through the lengthening grass, bowling each other over, baring their teeth and play snapping like Punch and Judy crocodiles. ‘Other Cooper’ barrels over to us from across the field – a 7 month old Ridgeback, muscular and majestic, a rippling red, all strength and no control. He jumps up at me, winding me and the dogs are soon a squirming mess of limbs and teeth in the grass.

Out on the lane I meet an older man, a backpack on his back, setting off up the hill. He tells me how he misses his wife, and his dog, ‘I cried more when he died than I did my parents,’ he confides. ‘Having a dog does make you get out,’ I say. ‘Oh, I don’t need a dog to do that,’ he replies, ‘but I miss the pub. It was an hour and a half of socialising every day.’ We all miss the pub.

The garden

It was the garden that persuaded me to take on the challenge of this house. This house that I feel overwhelmed by but that I am grateful for. I am living out there, finding solace in the busyness of spring and the challenge of a garden untended for years. It is hard not to feel guilty for having access to outside space when so many people are cooped up in flats and cities and I think of them each day. If I could share the space I would. Instead, I garden for wildlife, reasoning that this is the best contribution I can make to our collective wellbeing.

The activity helps to keep anxiety at bay. I shape things, pretending that I have some control. I think of those who have gardened here before, knelt where I am kneeling, dug where I am digging, moving the stone from this place to that, carefully removing the worms from the spade’s path, watching the robin creep ever closer to bob in and snatch some unseen grub before feathering away. Others have shaped the garden how they wanted it to be and nature has put it back again. I like to think that this might be what is happening globally, in the light of the pandemic, but with the loss of so many lives it is the redressing of a balance that it’s hard to feel entirely positive about.

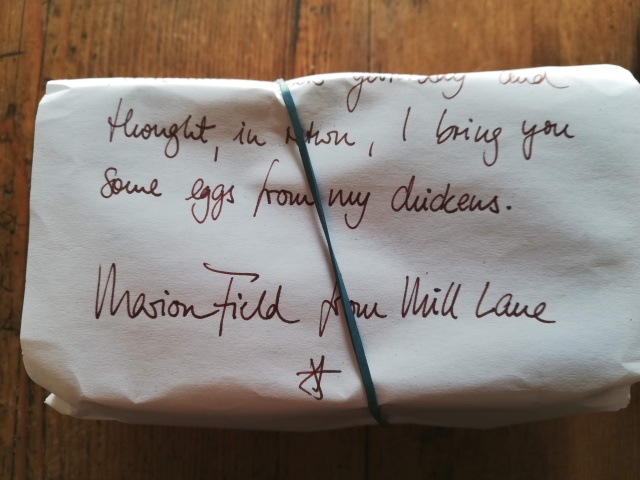

When we moved in, back in the autumn, I pulled Jersualem artichokes tubers from the earth in their dozens. Now they were sprouting in a sack in the shed. They have a lovely tall yellow flower, like a delicate sunflower, spread easily and their tubers are a versatile vegetable. Last week I put the tubers out on the front doorstep for passersby to take as they pleased. Opening the front door a few days later I found a box of fresh hen’s eggs left in exchange, with a note written in beautiful brown ink in a friendly hand from a neighbour. Even in isolation I am feeling the kindness of strangers.

Birds

After a day of working in the garden we sit and watch the soap opera of the birds. There is a dead crabapple tree by the wall towards the bottom of the lawn which I decided to leave as a wildlife habitat. I have planted out the climbing roses, hoiked from house to house in pots, beneath it to scramble up its branches and hung bird feeders. They come each morning and afternoon in a flit and a flurry to feed. The chaffinches are the drama queens, arriving in noisy squalls, bickering and fighting, falling to the floor in tiny dog-fights, kicking up clouds of dust. The robins are cheeky, balancing on the mower, the pea sticks, to eye us beadily before dropping to the beds to pull at worms and creatures in the chippings.

The goldfinches arrive in mobs, like red flashed pirates, an unruly congregation chit chatting and scuffling in the slow-to-green Cypress tree as they wait their turn on the feeders. They cast showers of sunflowers seeds onto the ground to spring up as little green shoots. They have found the few apple blossoms on the trees in the orchard and Glen tells me again how his father used to shoot finches for such sins in the past. We have noticed the first swallows sailing the warm air currents overhead in the evenings, a swirl of ten buzzards together over the fields and an ever-growing descant of lark song over the rape fields. As we sit and drink a beer we hear the soothing call and respond of the wood pigeons in the yew tree, ‘If you knew Suzy, like I knew Suzy…’

It is the blackbirds that make themselves most obvious, singing at day’s beginning and close from the yew tree; a full-throated cascade. A male blackbird dives back and forth across the garden each day as I dig, cramming his beak with worms to take back to his young. He has a daily ritual as the sun begins to dip, swooping in for a bath in the old china wash bowl I have sunk into the ground, filling and surrounding it with stones to ensure that anything that goes in can get out again. Dive, splash, ruffle, he goes, hopping up to the branches of the witch hazel to shake the water from his feathers. The blue tits and sparrows drink there, as does Cooper and I hope that the hedgehog and the slow worms that are emerging, have found their way to it, too.

Primroses and Panic

At dusk there has been a golden light in the garden. Primroses have festooned the bank sloping down to the road and now bluebells and cow parsley have sprung up in the shade of the beech and the limes as they slowly unfurl, the light from the setting sun giving them an other-worldly aura. We have planted over 30m of native wildlife hedge; hawthorn, blackthorn, dog rose, hazel, privet, field maple and guelder rose up there at the top and I have planted seeds, little acts of faith in the future. My sleep has improved, my panic-induced bouts of asthma all but disappeared.

Keeping it on the level

Mr Newton left us one of a pair of urns, of sentimental value to him and his family, as testament to his affection for the house and garden. Last week I dragged the urn to the centre of the lawn and balanced it on some pieces of sand stone, thinking that, at some point, I would make it more level, but that for now, it would have to do. I have planted it with a purple sage and sedum and a yellow and lime-green euphorbia that the evening light catches, making it glow. I have always driven my mum mad with my slap-dashedness, (a quality I like to think of as creative bravado). To her frustration I am very like my grandmother, Lorna. Anyone that knew Lorna would tell you that she was always beautifully dressed, usually complete with a hat and buttonhole. If you looked really closely, though, sometimes you might find that she had a ladder in her tights or a beetroot stain on her chin, that her hair was escaping from its bun in flyaway wisps and she had mud on her shoes from gardening in them. I am embracing my ladders and beetroot stains. Glen is more of Mum’s persuasion, so on seeing my wonky effort, he spent happy hours rectifying it; digging, levelling and replacing the urn until it looked as if it had always been there. My heart almost burst as I watched him in the heat dragging, digging and firming, checking over again with his spirit level that it was straight.

The close of day

As the light softens we watch the slow amble of the cows on the sloping fields opposite, young calves, from the local dairy, Sandford Gate. The green slopes are dotted with oaks, their shadows growing long on the ridge between the hills’ fold. The ridge is the sort of shape you would make by pushing your hand through wet sand to make a furrow.

There are primroses in the lawn, wasps buzzing in and out of holes in the stone wall behind us, mouse or vole or shrew holes, I don’t know which, beneath our chairs. The light illuminates the lettuces, fattening each day in the border amongst the perennials and herbs, looking like the lettuces in my Ladybird book of Rapunzel, the ones that her father stole from their neighbour to satisfy his wife’s craving. At this rate we shall have ten fat lettuces all ready at the same minute. Salad, anyone?

When the light has dimmed and the bats are beginning to dive in the courtyard we go down into the dark of the house. It is not a house for searching out the light, but at night when we return to it, like returning to another world, our dim cave, it wraps itself around us, comforts us. We could have bought a bungalow, a modern terrace for the same investment as this awkward house, but then we would not have this garden, which has saved me, saved us both.

Glen

As I work in the garden I can hear Glen up on the wooded part by the path where he is busy chopping logs and planting out the hedge, talking to passersby just as his dad has always done at Yew Tree Cottage. ‘Who was that you were talking to earlier?’ I ask when we are back together. ‘I don’t know their name,’ he says, ‘but we always have a chat.’ He is introducing me to the language of his childhood in the tools that he is using; billhook, fagging hook, mattock. I collect them for a poem, as I collect the wild flowers growing under the trees, to press.

One older lady comes by often, to walk the path to the commemorative bench for her friend. It is just through the gate into the field and looks out over the valley. She has a kind face and a soft voice. She tells me of her husband, at home now with Alzheimers, how they used to keep bees and sell the honey in the shop, how she misses the bees, but notices them more now, what it is that they are feeding on and when. ‘We have been very blessed,’ she says, smiling and walking on.

Glen has picked pocketfuls of wild garlic, or ramsons, that grow down by the river, to make pesto with walnuts to stir into pasta, to make a chicken pie, to wrap the Easter lamb with. Easter lunch had to wait until Easter Monday this year as Glen fell ill, suddenly, on Easter Day. It turned out to be a migraine, something he hasn’t experienced for 40 years, but his sudden deterioration had me jangled and concerned. These are charged times, making us all more jumpy and uncertain. I found myself having to resist a rising sense of panic and to think about a situation that so many thousands of others have had to face. What if it was something serious? What if I had to leave him at a hospital and be parted from him? The healthcare professionals and 111 call handlers we spoke with were all brilliant and I felt a renewed gratitude for them and also for Glen, when he recovered, later that evening. For at least a few hours I even kept my promise to be nice to him forever.

Posted byysella1Posted inchange, Devon life, Gardening, nature, Wild flowers, wildlife, wildlife gardeningTags:change, nature, wildlife gardening3 Commentson Small Offerings